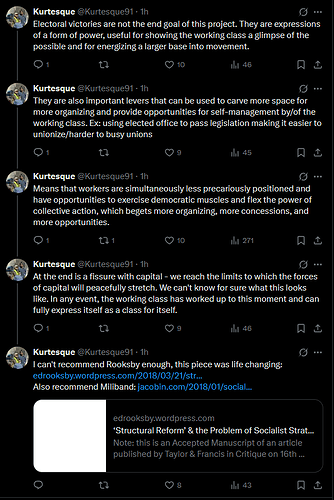

from the rooksby

Thus, after the Syriza experience, the radical left seems to be trapped in a strategic impasse. It is caught between an electoral strategy of reform, on the one hand, that, while it can clearly galvanise mass support, seems unable to break free of the structural limits of ‘parliamentary statism’ and a revolutionary strategy, on the other, that has very little resonance with workers today and probably never did have beyond the specific conditions of Russia in 1917. //

The terms of the problem, briefly, are that there is no realistic way to move straight to the ‘final aim’, but the process of attending to immediate problems – amelioration of the worst effects of capitalism by means of reform – tends to lead to incorporation within a system that has definite structural limits and embedded systemic mechanisms to enforce these (capital flight, inflationary pressure, balance of payments crises for example). // It is rooted in capitalist control over the investment function which provides the capitalist class with what is effectively power of veto over any government policy that undermines capitalist domination. In this way any government that introduces measures that seriously undermine (or threaten to seriously undermine) capital accumulation will soon be faced with a serious crisis of disinvestment, flight of capital, attacks on the currency and so on and hence come under enormous pressure to reverse those measures.[9]

What emerged, organically, out of the day-to-day struggles of the Greek working class was not a tendency toward direct confrontation with the existing state system as such … but a more or less spontaneous move toward support for the idea of a left government operating within existing parliamentary institutions as the next concrete step in the process of struggle in that country. While Syriza successfully grasped this dynamic (indeed helped to galvanise it) other organisations of the left were unable to relate to it. //

Syriza did, indeed, fail in office, but at least their failure was a failure of some significance, rather than the pre-emptive failure of effectively rejecting in the first place the very possibility of taking power and really starting to confront concrete problems of social transformation. Indeed, Syriza’s message and its approach of tapping into social movements, seeking to articulate them into a coherent political project and orienting on government resonated with the Greek population precisely because Syriza were prepared, no matter how imperfectly, to confront the question of political power rather than dodge it.

For those associated with the Left Platform, such as Stathis Kouvelakis for example, the prospect of a Syriza government raised the possibility of a dialectic between the activities of elected representatives within the state and social struggles from below. Kouvelakis hoped that Syriza in office would take initiatives to ‘open up a space for social mobilization’[22] and thus catalyse a renewed and radicalised wave of popular mobilisation that would both provide a base of support for the government while also pushing it on in the face of opposition from ‘the Troika’, forcing it to stick to its promises.

This dialectic, it was envisaged, would interact with a second dynamic in which the government’s programme of reforms would soon bring it into direct confrontation with the forces of domestic and international capital, thus necessitating the further radicalisation of this programme – and of popular struggles in support of them- if those initial reforms were to be carried through and defended. //

Crucially, this dialectical process of radicalisation would be rooted in – indeed, could only begin from – an initial programme of relatively ‘modest’ policies. Indeed, the defining feature of Syriza’s programme as it entered government was that it corresponded to the immediate and pressing needs and demands of ordinary Greeks – for jobs, better wages, affordable food and housing and so on. It was precisely because of this correspondence that Syriza’s programme resonated so successfully with Greek voters, bringing the party to victory in the 2015 general election and thus putting real change on the agenda in a way that ostensibly ‘radical’ but wholly abstract revolutionary demands with little political traction never could. However, it was also clear to Left Platform thinkers that for all the eminently reasonable and sober pragmatism of the party’s programme, these measures would, if implemented, soon run up against the limits of what European capital and its political representatives would accept. In this respect, Syriza’s programme successfully located what Slavoj Žižek has called a ‘point of the impossible’.[24] This is something in the field of politics or the economy that ‘you can (in principle) do but de facto you cannot or should not do it – you are free to choose it on condition you do not actually choose it’.[25] Pressing forward on such a ‘point of the impossible’, Žižek suggests, has a kind of demystifying effect that reveals the limits of a system and the relations of unfreedom and domination that undergird it. //

The vision of militants such as Kouvelakis, then, was that by carrying through on these ‘point of the impossible’ demands, a struggle for ‘modest’ reforms within capitalism would escalate organically into a more and more consciously and openly anti-capitalist struggle. // Certainly Kouvelakis believes that had a different strategic outlook prevailed among the leading forces in Syriza the coming to power of a left government in Greece might have opened up a process of radical social change in that country and beyond.[28]

What is more, this strategic outlook appears to offer the prospect of a way out of the strategic impasse identified by Sassoon – it seems to provide, that is, a possible route to bridge the gulf between immediate demands and the end goal of socialist transformation, between reform and revolution.